Bulletin photos by Nadine El-Bawab

‘This is not personal; we have questions to ask. I’m not trying to be a jerk, but I’m not trying to be their friend.’

— Eric Rasmussen,

Investigative reporter,

Boston 25 News

There are no dumb questions,

and other interviewing advice

By Jesse Goodman

Bulletin Correspondent

Among the tips Eric Rasmussen delivered to journalists at the recent New England First Amendment Institute was this answer to a query about what interview questions to avoid:

“The only dumb question is the one you don’t ask. If it doesn’t end with a question mark, you probably won’t get what you want.”

Rasmussen, an award-winning investigative reporter with Boston 25 News, had much advice to share on his topic of “The Confrontational Interview and Transition to Audio or Video” at the Institute Oct. 31 at Northeastern University.

“Interviews take on all shapes and sizes,” Rasmussen said. “Every interview, almost without exception, doesn’t go (according) to expectation.”

Rasmussen, a news anchor in Orlando, Fla., Chico, Calif., and Champaign, Ill, before returning to Boston, the home of his alma mater, Boston University, recommended identifying what kind of interview is planned.

He mentioned three kinds: Interviews for accountability (Why was this person let out of jail with this kind of record?); emotional (How does it feel to get out of jail?); or informational (When were you released from jail?).

Rasmussen showed examples of his work. They included an unscheduled interview with a man using an alias to sell food stamps on Facebook as a part of a report on the abuse of food stamps in Massachusetts. Rasmussen figured out who the man was through his friends on Facebook, and tracked him down before confronting him.

That doesn’t have to be the case for all interviews, Rasmussen said.

Rasmussen showed another clip of him talking to Boston Mayor Marty Walsh about the building of a fence to keep drug users away from a particular area, only to have them use another end of the same street. Walsh’s team didn’t want him to meet with Rasmussen at first. But after Rasmussen interviewed Walsh’s chief opponent in the mayoral race, Tito Jackson, Walsh was ready to sit down with Rasmussen and talk about the fence.

“This is not personal; we have questions to ask,” Rasmussen said. “I’m not trying to be a jerk, but I’m not trying to be their friend.”

Rasmussen’s other tips included structuring a story with characters, context, conflict, and resolution.

He recommended reviewing quotes from the person you’re interviewing, to come up with additional questions. Rasmussen suggested trying to make most questions open-ended, to encourage the interview subject to respond more expansively.

Rasmussen urged never allowing someone being interviewed to get away with saying something that isn’t true.

“You can really miss out if you don’t listen to what they say,” Rasmussen said.

Rasmussen suggested getting contact information to follow up with the person interviewed, even if it’s just to let the person know that the piece has been published or aired.

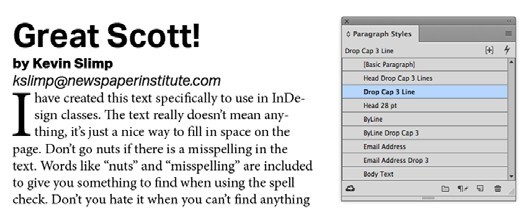

Presenter Eric Rasmussen provides interviewing tips to his audience at the New England First Amendment Institute.

‘You can really miss out if you don’t listen to what they say.’

— Eric Rasmussen

Woody Klein has retired as a news columnist for the Westport News after 50 years. Klein’s career began as a reporter for the Mount Vernon (N.Y.) Daily Argus. He then was a night police and general assignment reporter for The Washington Post for a year and a half before joining the New York World-Telegram & Sun, where he covered poverty, politics, housing and civil rights. From 1992 to 1997, beginning at age 63, Klein was the Westport News’ editor. He oversaw reporters who won many awards for their work. One piece, Behind Closed Doors, about abuse of women in their homes in Westport and Weston, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. Klein wrote a 400-page book about the town’s history, titled “Westport Connecticut: The Story of a New England Town’s Rise to Prominence” and published in 2000. Klein has won numerous awards for his writing. His 10-part series, I Lived in a Slum, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 1965. In 1964, Klein’s first book, “Let in the Sun,” was published. It told the story of his time as an undercover reporter in some of New York’s worst tenements. He wrote eight more books, with themes such as politics and poverty, while at the Westport News. After his time at the World-Telegram & Sun, Klein spent three years as then-New York Mayor John V. Lindsay’s press secretary. Klein later joined IBM, where he spent 24 years in communications for its manufacturing, development and marketing divisions. His last role at IBM was editor of Think magazine, the company’s international employee magazine distributed in more than 170 countries. Klein began his column, Out of the Woods, in the Westport News soon after he began working at IBM.

Woody Klein has retired as a news columnist for the Westport News after 50 years. Klein’s career began as a reporter for the Mount Vernon (N.Y.) Daily Argus. He then was a night police and general assignment reporter for The Washington Post for a year and a half before joining the New York World-Telegram & Sun, where he covered poverty, politics, housing and civil rights. From 1992 to 1997, beginning at age 63, Klein was the Westport News’ editor. He oversaw reporters who won many awards for their work. One piece, Behind Closed Doors, about abuse of women in their homes in Westport and Weston, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. Klein wrote a 400-page book about the town’s history, titled “Westport Connecticut: The Story of a New England Town’s Rise to Prominence” and published in 2000. Klein has won numerous awards for his writing. His 10-part series, I Lived in a Slum, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 1965. In 1964, Klein’s first book, “Let in the Sun,” was published. It told the story of his time as an undercover reporter in some of New York’s worst tenements. He wrote eight more books, with themes such as politics and poverty, while at the Westport News. After his time at the World-Telegram & Sun, Klein spent three years as then-New York Mayor John V. Lindsay’s press secretary. Klein later joined IBM, where he spent 24 years in communications for its manufacturing, development and marketing divisions. His last role at IBM was editor of Think magazine, the company’s international employee magazine distributed in more than 170 countries. Klein began his column, Out of the Woods, in the Westport News soon after he began working at IBM. John Tabor is retiring as president and publisher of Seacoast Media Group, based in Portsmouth, after 40 years in newspapers. Seacoast publishes the Portsmouth Herald, Foster’s Daily Democrat of Dover, and weeklies in New Hampshire and Maine. It also is a commercial printer whose clients include the New Hampshire Union Leader of Manchester; The Sun of Lowell, Mass.; and the Sentinel & Enterprise of Fitchburg, Mass. Seacoast provides digital marketing, direct mail and commercial delivery services too. After graduating from Yale University in 1977, Tabor interned at The Providence (R.I.) Journal. He then joined the copy desk at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and later became a police and court reporter for the Arizona Star of Tucson. After that, he bought a weekly for Mead Publishing of Lakeport, Calif., with a college friend. The paper increased its publication to five days a week before Tabor sold his share in the weekly to Mead. Tabor then published the Portsmouth Press with the former Ottaway Newspapers in 1987, initiating a newspaper rivalry with the Portsmouth Herald. An economic recession that began in 1991 resulted in the closing of the Portsmouth Press in 1993. Tabor briefly became general manager of the Pocono (Pa.) Record. In 1994, he was named publisher of Rockingham County Newspapers, including the Exeter News-Letter, the Hampton Union and the Rockingham News. In 1997, in a newspaper swap between the owners of Rockingham County Newspapers and the Portsmouth Herald resulted in the Herald merging with Rockingham County Newspapers, Seacoast Media’s first website, Seacoastonline.com, was launched that year. In 2001, Seacoast acquired the York (Maine) Weekly and York County Coast Star of Kennebunk, Maine

John Tabor is retiring as president and publisher of Seacoast Media Group, based in Portsmouth, after 40 years in newspapers. Seacoast publishes the Portsmouth Herald, Foster’s Daily Democrat of Dover, and weeklies in New Hampshire and Maine. It also is a commercial printer whose clients include the New Hampshire Union Leader of Manchester; The Sun of Lowell, Mass.; and the Sentinel & Enterprise of Fitchburg, Mass. Seacoast provides digital marketing, direct mail and commercial delivery services too. After graduating from Yale University in 1977, Tabor interned at The Providence (R.I.) Journal. He then joined the copy desk at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and later became a police and court reporter for the Arizona Star of Tucson. After that, he bought a weekly for Mead Publishing of Lakeport, Calif., with a college friend. The paper increased its publication to five days a week before Tabor sold his share in the weekly to Mead. Tabor then published the Portsmouth Press with the former Ottaway Newspapers in 1987, initiating a newspaper rivalry with the Portsmouth Herald. An economic recession that began in 1991 resulted in the closing of the Portsmouth Press in 1993. Tabor briefly became general manager of the Pocono (Pa.) Record. In 1994, he was named publisher of Rockingham County Newspapers, including the Exeter News-Letter, the Hampton Union and the Rockingham News. In 1997, in a newspaper swap between the owners of Rockingham County Newspapers and the Portsmouth Herald resulted in the Herald merging with Rockingham County Newspapers, Seacoast Media’s first website, Seacoastonline.com, was launched that year. In 2001, Seacoast acquired the York (Maine) Weekly and York County Coast Star of Kennebunk, Maine Melvin Stone

Melvin Stone Richard E. Rappoli

Richard E. Rappoli William F. Dougherty

William F. Dougherty Frank Edward Keane

Frank Edward Keane Derek C. Gentile

Derek C. Gentile  Karlene Kelley Hale

Karlene Kelley Hale Mildred Cole Péladeau

Mildred Cole Péladeau Anthony Randolph ‘Tony’ Jenkins

Anthony Randolph ‘Tony’ Jenkins Christina Caturano

Christina Caturano Robert J. Kmon Sr.

Robert J. Kmon Sr.

Jeff Otterbein has retired as sports editor of The Hartford Courant after 27 years. Dan Brechlin has been named to replace Otterbein as sports editor. Otterbein began in the Courant sports department in 1985 and has been sports editor since 1990. Otterbein has won the Associated Press Sports Editors Triple Crown for Top 10 daily section, Sunday section and special section four years in a row. Before his time at the C

Jeff Otterbein has retired as sports editor of The Hartford Courant after 27 years. Dan Brechlin has been named to replace Otterbein as sports editor. Otterbein began in the Courant sports department in 1985 and has been sports editor since 1990. Otterbein has won the Associated Press Sports Editors Triple Crown for Top 10 daily section, Sunday section and special section four years in a row. Before his time at the C ourant, Otterbein was assistant sports editor at the Sun Sentinel of Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Brechlin was previously the deputy metro editor for the Hartford Courant. Before joining the Courant, he was city editor for the Record-Journal of Meriden for six years. He was a reporter there until 2014 and then city editor from 2014 until 2016. He also has been a reporter for the Southington Citizen and the Plainville Citizen.

ourant, Otterbein was assistant sports editor at the Sun Sentinel of Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Brechlin was previously the deputy metro editor for the Hartford Courant. Before joining the Courant, he was city editor for the Record-Journal of Meriden for six years. He was a reporter there until 2014 and then city editor from 2014 until 2016. He also has been a reporter for the Southington Citizen and the Plainville Citizen.

Members of the audience at Glen Johnson’s talk listen intently

Members of the audience at Glen Johnson’s talk listen intently

The four panelists at the discussion on using analytics in news decisions, from left: Tom Zuppa, David Colantuono, Jason Tuohey and Carlos Virgen.

The four panelists at the discussion on using analytics in news decisions, from left: Tom Zuppa, David Colantuono, Jason Tuohey and Carlos Virgen.

We’re a big part of the fix for ‘junk news’

Gene Policinski

Inside the First Amendment

Gene Policinski is chief operating officer of the Newseum Institute and senior vice president of the Institute’s First Amendment Center. He can be reached at gpolicinski@newseum.org.

Follow him on Twitter:

@genefac

Let’s stop talking so much about “fake news.”

Not that we should ever cease identifying, talking about or countering misinformation, be it accidental error, the result of negligent work, or deliberately false — to which we must now add propaganda tactics aimed at destabilizing our democracy.

We face all those types of misinformation today; amplified as they are by platforms that allow for instantaneous, worldwide communication.

But the term “fake news” no longer has any real meaning as a national concern or a problem to be dealt with. The term has become far too politicized and much too imprecise, now serving as a catch-all for information anyone sees as divisive, disagreeable, biased or plain wrong. Instead, I prefer a term offered by my Newseum Education colleagues: “junk news.”

Regardless of what we call it, less talk and more action on misinformation is where our focus ought to be. Media Literacy Week, which took place Nov. 6 through 10, is as good a time to start as any.

NewseumED, the Newseum’s nonpartisan education arm, offered information and tools to help students — and all of us — navigate today’s complex media landscape. Its collections of resources are all aimed at helping us understand how news is made and how we can take a more active and responsible role in the information cycle. That includes having the skills to evaluate information, filter out fake news, separate facts and opinions, recognize bias, detect propaganda, spot errors in the news and take charge of our role as media consumers and contributors.

As junk news continues to infiltrate the newsfeeds of millions of social media users, education and awareness have become the best line of defense against the spread of misinformation and disinformation. Where journalists once served as the “gatekeepers” of society’s daily information consumption, today anyone with internet access can create and distribute content, and spread information by sharing it on social media.

For many people, that’s more comfortable and a better option: the power to choose and shape what we need to know, rather than having it fed to us by a select few. But with that power should come a greater sense of responsibility to draw our news from as many reliable, diverse sources as we can.

Failure to do that has created the now-infamous condition in which social media’s omnipresent algorithms track our every keystroke to present us with news that we “like” — or in other words, news that plays to our existing opinions and biases.

Sure, there was a time when readers would settle on a favorite TV network or, in an even earlier era, a favorite radio station for the nightly news. Newspaper readers in communities where there were multiple daily publications would subscribe to one over the others. Much of the non-local news, for good or bad, contained the same information — very often taken from wire services that prided themselves on their ability to “get it first, get it right — but above all, get it right, first.” Those were the days when CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite was called the “most trusted man” in the nation, by virtue of that news media mantle.

In today’s news world, where those long-standing print and broadcast news outlets are barely standing, and new media players have yet to show the depth or credibility it takes long to develop, we as consumers must take less on “faith” and more on “fact.”

For their part, news operations, think tanks, social media companies and others are working on ways to help consumers play a more responsible role in the daily news cycle. Verifying stories and tightening ethical standards are good starts, but significant obstacles lay in the path — namely, the declining revenue and resources of traditional press organizations, and the new Web-based media economy that depends on eyeballs and clicks. In such an environment, thorough “accountability” reporting — often dull but always necessary — has fallen by the wayside.

There are some signs that people are rethinking a reliance on just one site, which is a good first step to improving our news diet. According to the Pew Research Center, about a quarter of all U.S. adults (26 percent) get their news from two or more social media sites, up from 15 percent in 2013 and 18 percent in 2016. But consumers shouldn’t stop with just “more” — our daily intake needs to consist of varied, credible sources. Otherwise, consumers trap themselves in a news bubble or echo chamber, in which they only see information that confirms and reinforces their opinions instead of challenging them.

At a recent forum on First Amendment issues and fake news, I advanced a long-held theory of mine that eventually news consumers will demand information on which they can rely, and will over time migrate to those sources; that credibility will be the news currency of the 21st century

But it’s no longer the province of news providers alone to build that demand. Individual consumers must join in that effort by getting savvier about the news. In a twist on an old saying, “Let the buyer be aware.”