Fall conference round table reflects on handling public safety agency handlers

By NENPA Vice President John Voket

Associate Editor – The Newtown Bee (CT)

Looking around the sparsely populated “round table” of about a dozen attendees at an opening session of the New England Newspaper & Press Association’s 2017 Fall Conference, Newburyport Daily News Managing Editor Richard K. Lodge referenced the subject at hand – how the ongoing squeeze in newsroom staffing mirrored similar challenges police agencies are having responding to growing demands for public information.

That October 12 session at the Natick Crowne Plaza, presented by the New England Society of Newspaper Editors (NESNE), was entitled “How to handle the handlers: PR & public safety – bridge or barrier to info?”

Famously or notoriously, relationships between press and police agencies have ranged from functional to downright confrontational – if not nonexistent. But public demand for information from local police agencies has increased exponentially in the age of social media and 24-hour news cycles.

That “taxpayer” thirst for police information, and the more constrained ability for many news agencies to gather, analyze, and relate that information has paved the way for former police reporter and now police information purveyor John Guilfoil who heads up John Guilfoil Public Relations.

He was among panelists for the round table along with a pair of veteran police reporters Norman Miller of Metrowest Daily News, and the Boston Globe’s Emily Sweeney. They were joined by Brian Kyes, president of the Massachusetts Major City Chiefs Association and Chelsea Chief of Police.

“There are fewer people in newsrooms and those fewer people as you know have a lot of different duties they are asked to perform,” Lodge said. “John’s public relations group saw a need. And what’s I think it’s done is pick up the slack on things that might not have been covered, or that fell into the weeds. Now there is actually someone coming up with that information.”

On the other hand, Lodge like many journalists, said “I grit my teeth over public relations, to be honest.”

Remote control

Chief Kyes said he believes in having a “strong bridge” between his department and the media, and recalled an active shooter situation his department was facing one day while he was traveling.

As gunshots rang out across the neighborhood, media converged on the scene and the chief was able to watch it all play out in a live camera feed from the scene from Martha’s Vineyard. With that perspective and his immediate contact with command supervisors at the scene, Chief Kyes said he was better able to control the flow of immediate press queries remotely.

“The old school – commanders would say ‘I’m too busy’ or ‘I don’t have time’. But the media represents the public and the public wants to know what’s going on,” Chief Kyes said. “So I’m getting information and I’m sending out tweets in real time, just to keep the story straight.

“In today’s day and age,” he added, “to be able to control the message and building that strong bridge with the media is super important.”

Chief Keys said he has been contracting the Guilfoil agency for three years and believes its services complement the public information being provided directly from a designated Chelsea police officer.

Guilfoil said after seven years at The Boston Globe and having served as Deputy Press Secretary for the late Boston Mayor Thomas M. Menino, he has “seen how effective good, sound public relations can be.”

But today, Guilfoil said he is witnessing a “major disconnect” between that level of good sourcing and news organizations.

“If you are a good PR person, you are not a gate keeper – you’re a gate opener, a facilitator,” he said. Guilfoil added that press liaisons are also challenged given the quick turnaround of staff at news organizations where both are trying to build some degree of trust and rapport.

“Relationship-building has become the lost art of humanity,” Guilfoil said.

‘All the facts’

Guilfoil said his goal is to help bridge the information gap between public agencies and the public by consulting on and maintaining more than 100 police and fire department web sites. His company has also counseled countless public officials who hated the idea of social media to effectively employing Facebook, Twitter and other platforms – many on a daily or even hourly basis when needed.

Sweeney said she wasn’t surprised to see public safety agency releases coming from Guilfoil, a former Globe colleague, noting how well-written they were containing “all the facts a reporter would want.”

But she also weighed the disadvantages of a former colleague representing so many public agencies she and her paper cover on a daily basis. The takeaway: “I gotta say, the advantages from my standpoint totally outnumber the disadvantages,” Sweeney concluded.

She noted that so many small safety agencies, like newsrooms, are so thinly staffed, they may not have a dedicated public information officer. That makes her even more appreciative of those safety agencies that can not only respond to basic breaking news inquiries, but provide deeper sourcing for features and enterprise pieces.

Miller agreed after beginning to receive releases from Guilfoil.

“They come in handy,” he said. “It’s good to get these press releases in our e-mail, we don’t have to dig it up.”

A downside Miller sees, however, is with smaller agencies during breaking news events.

“I’ll call with follow-up questions, and they’ll say, ‘yeah I sent a release.’ But I have follow-up questions,” Miller lamented. “As a reporter I may need one little piece of information. So some small departments fall behind the fact that they will be having another release coming out in an hour. That’s what they rely on instead of building that face to face.”

Are releases a shield?

Suspecting that some departments use their release schedule and Guilfoil’s agency as “a shield,” Miller said nonetheless he sees the company’s output as an asset when it comes to getting details for his police reporting.

Lodge probed further asking Guilfoil if he thinks his clients use the outside agency as a shield to deflect requests to clarify immediate details absent in a release from media callers.

Chief Kyes interjected that during the early minutes of breaking situations, he’s juggling calls from the scene, as well as from the media and city officials also calling for information.

“There’s a lot going on, a lot of moving parts,” the police chief said, recalling a situation where leading too quickly on releasing details at a shooting scene resulted in a retraction shortly after the incorrect number of victims was hastily released.

“I know there is a race to getting that information out, but there is a delicate balance of getting it correct and getting it out in a timely member,” he said, empathizing with reporters who may have to deal with many different agencies each with its own policies on what information can be released – especially in braking situations.

Guilfoil said he hates corrections on correspondence from his agency because it degrades credibility across all the outlets receiving that erroneous information.

At the same time, he countered that as a result of being retained by many smaller agencies, “a lot are getting information out now that we’re not before.”

The ‘death of journalism’?

Miller said as a seasoned reporter, he is concerned young and overwhelmed media staffers will opt to falling back on releases versus building professional rapport with police agency sources.

Sweeney picked up on that observation saying she likes going out and making those face to face contacts, and she has been gratified that her editors have supported her taking that time.

Ann Wood of the Provincetown Journal said even with just one reporter at her small publication, she was observing the round table conversations feeling “totally disturbed” about “getting news from a public relations department.”

Wood said that a good release could spark an editor or reporter to go out and get the story details themselves, “but to take something off of somebody at a company who has been paid to send it to you is like, anti-journalism to me.”

The Provincetown editor said her greatest concerns are accuracy – and thoroughness.

“It’s accurate to what the people who are paying you want it to be,” she said. “To treat it as a legitimate source, to me, is like the death of journalism.”

A substitute PIO

Guilfoil said that a lot of departments he does not contract with have civilian agents providing public information, and many others have sworn officers in that position.

“I don’t believe I am different that any other source,” Guilfoil said. “I am the direct source. All I want to do is be looked at as a substitute PIO (public information officer).”

Attendee George Brennan also with the MV Times said in his experience, police agencies and chiefs who maintain good press relations see the benefit of building and maintaining that bridge. He said on par, it said reporting on those departments has much greater value to their communities, “even with stories where a police officer is in trouble for something, they come across so much better.”

Representing around 200 agencies across eight states, Guilfoil said his level of interaction with clients ranges from maintaining daily communications, social and web responsibilities to being on one highly limited retainer at $100 annually.

And he hasn’t shied away from dropping clients, either. “We had an issue where our philosophies didn’t match up,” Guilfoil offered.

Ultimately, he said any hesitancy safety agencies may have providing details to the press is borne from the fear of releasing incorrect details.

“A police department wants to get it right,” he said. “A lot of that is bridging the gap between ‘I’m afraid of the press,’ or ‘my last chief got burned,’ to getting a lot of chiefs out of their comfort zone, or a captain, or lieutenant, or a sergeant – putting them out there in front of the cameras and stating the facts.

“Your department reflects well because of that.”

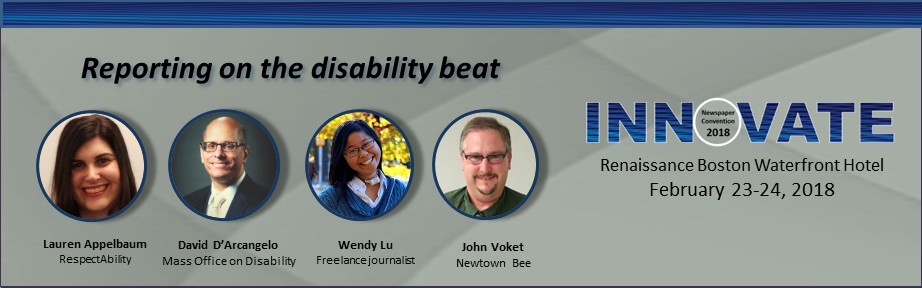

I am a national reporter based in New York City. I’ve written for The New York Times, Teen Vogue, Bustle, Columbia Journalism Review, Newsday, and many others. I write about a wide range of health disparities and social issues within disability communities, including topics like family, education, relationships, gender dynamics, and policy. I’m also a speaker on living with a disability, inclusive feminism and best practices for reporters covering disability issues.

I am a national reporter based in New York City. I’ve written for The New York Times, Teen Vogue, Bustle, Columbia Journalism Review, Newsday, and many others. I write about a wide range of health disparities and social issues within disability communities, including topics like family, education, relationships, gender dynamics, and policy. I’m also a speaker on living with a disability, inclusive feminism and best practices for reporters covering disability issues.

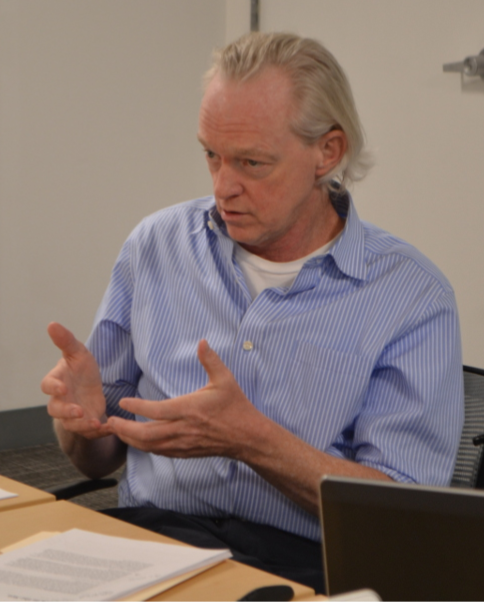

Rezendes’ hunch proved to be right; his investigation led to the discovery of Bridgewater State prison guards using four-point restraints and isolated containment, methods of restraining the mentally ill that were not common practices around the country.

Rezendes’ hunch proved to be right; his investigation led to the discovery of Bridgewater State prison guards using four-point restraints and isolated containment, methods of restraining the mentally ill that were not common practices around the country.