Judith Meyer, executive editor of the Sun Journal of Lewiston, Maine, embraces Justin Pelletier, the Sun Journal’s managing editor, in celebration of her receving the Judith Vance Weld Brown Spirit of Journalism Award.

‘Mentoring happens in the moment. Mentoring happens every day.’

— Judith Meyer,

Executive editor,

Sun Journal,

Lewiston, ME

Words of passion, concern

echo at NESNE awards fete

By Kaitlyn Mangelinkx

Bulletin Correspondent

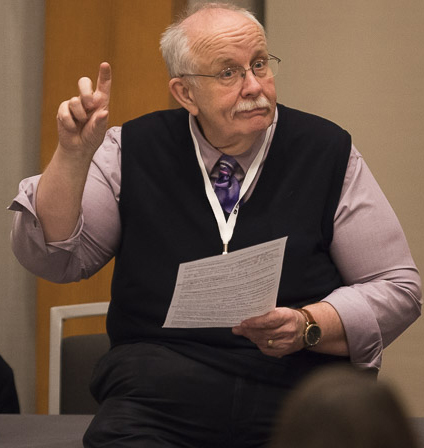

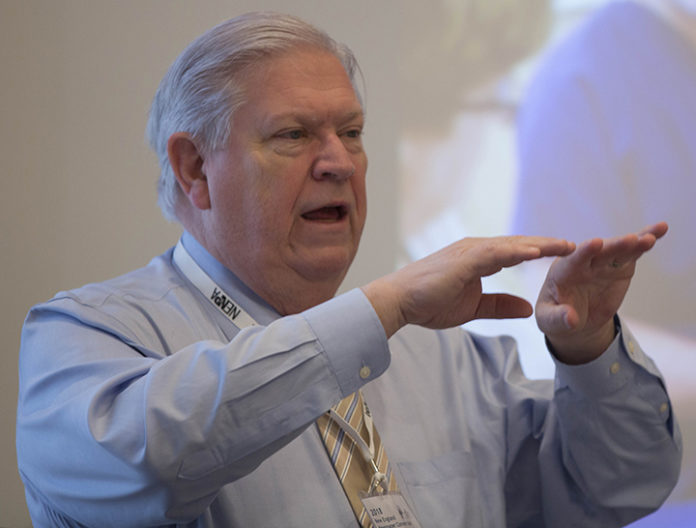

“The world would be a poorer place without (journalists),” Scott Allen, assistant managing editor of special projects at The Boston Globe, said, fittingly, in his introductory speech at the recent New England Society of News Editors awards ceremony.

Allen’s speech mentioned themes of concern that would be echoed by award winners who spoke after him.

The remarks of winners of the New England Society of Newspaper Editors awards indicated that journalism is more than a passion for them; it is an obligation.

The awards ceremony took place Thursday, April 19, at The Boston Globe. About 80 people attended.

The following received the five key individual awards:

New England Journalism Educator of Year

Kristen D. Nevious

Nevious, a journalism professor at Franklin Pierce University in Rindge, N.H., and director of its Marlin Fitzwater Center for Communication, was lauded for her dedication to students. She teaches courses focusing on innovation in journalism and on political

‘What hasn’t changed is the need for insatiable, trained journalists.’

— Kristen D. Nevious,

Journalism professor,

Director, Marlin Fitzwater Center for Communication,

Franklin Pierce University,

Rindge, N.H.

journalism.

Phyllis S. Zrzavy, a professor of communications at Franklin Pierce, introduced Nevious as a mentor for many student groups who offers students special opportunities, such as covering political primaries and listening to influential speakers. Zrzavy said Nevious draws speakers not only for her college students, in a series called “Tuesday Briefings,” but also for high school journalists around the country during a summer program. Nevious focuses on ensuring that all her students are prepared for a future of important work in the news industry, no matter what changes or innovations occur, Zrzavy said.

Nevious said in accepting her award that earlier in her career she taught students on manual typewriters.

“What hasn’t changed is the need for insatiable, trained journalists,” she said.

Nevious said that, despite the changes, she remains passionate about the impact journalism can have. She reflected on trips on which she brought students to cover political primaries and rallies. She views those opportunities as chances to spread her passion for journalism to the younger generation, moving them from students to professionals capable of making change.

Newsroom Rising Star

Amaris Castillo

Castillo is a reporter at The Sun of Lowell, Mass. She was nominated for the award by the Sun’s editor, Jim Campanini, who said Castillo “epitomizes what is really a pioneer in journalism.”

Castillo joined the Sun in 2017, moving from Florida, where she was known for a series called “Bodega Stories,” which she wrote on her own time by talking with residents of

Manatee County in Florida, where she was a reporter for the Bradenton Herald. Campanini said that, after seeing the Bodega series, he was thrilled to have Castillo’s perspective as a reporter in Lowell after she moved to Massachusetts, a point he mentioned when introducing her. Campanini said he was awed by the passion Castillo put into her work, creating “Bodega Stories” as a passion project to help spread the narratives of under-represented communities.

Since coming to the Sun, Castillo has continued her “gumshoe” reporting, talking to residents and gaining perspective as the first Spanish-speaking reporter at the Sun, a point of pride that Castillo and Campanini both mentioned in their speeches.

In her acceptance speech, Castillo said she is “proud to be a child of immigrants,” using that perspective to speak out about the concerns of Latino communities, both in Florida and Massachusetts. Castillo thanked those at the Sun for trusting her perspective, giving the example of a story she wrote during her lunch hour after talking to Puerto Rican residents in Lowell in the days before Hurricane Maria. The story was published on the front page of the Sun the next day.

Judith Vance Weld Brown Spirit of Journalism Award

Judith Meyer

Meyer, executive editor of the Sun Journal of Lewiston, Maine, received the award that honors the accomplishments of an outstanding female journalist in New England. Meyer was introduced by Justin Pelletier, the Sun Journal’s managing editor, who described Meyer’s impact in the newsroom. Under her leadership, the Sun Journal newsroom has learned the importance of passion, following in Meyer’s footsteps as she not only works as editor of the paper, but regularly covers stories herself, often winning awards for her work, Pelletier said.

In her acceptance speech, Meyer said she “fell into this crazy profession that we share 20 years ago, completely by accident.” She began as a freelancer, before finding her passion for journalism when covering a routine story. The story involved talking with the local medical examiner’s office, where Meyer found the cause of death for a local man. She was then contacted by the man’s mother, who had not been able to receive any explanation about her son’s death from the medical examiner’s office. That prompted Meyer to focus on the responsibility of journalists to ensure that government officials are held accountable.

Meyer also discussed mentoring younger journalists, something she views as an obligation to the future of journalism.

“Mentoring happens in the moment,” she said. “Mentoring happens every day.”

The following other award winners were honored at the event:

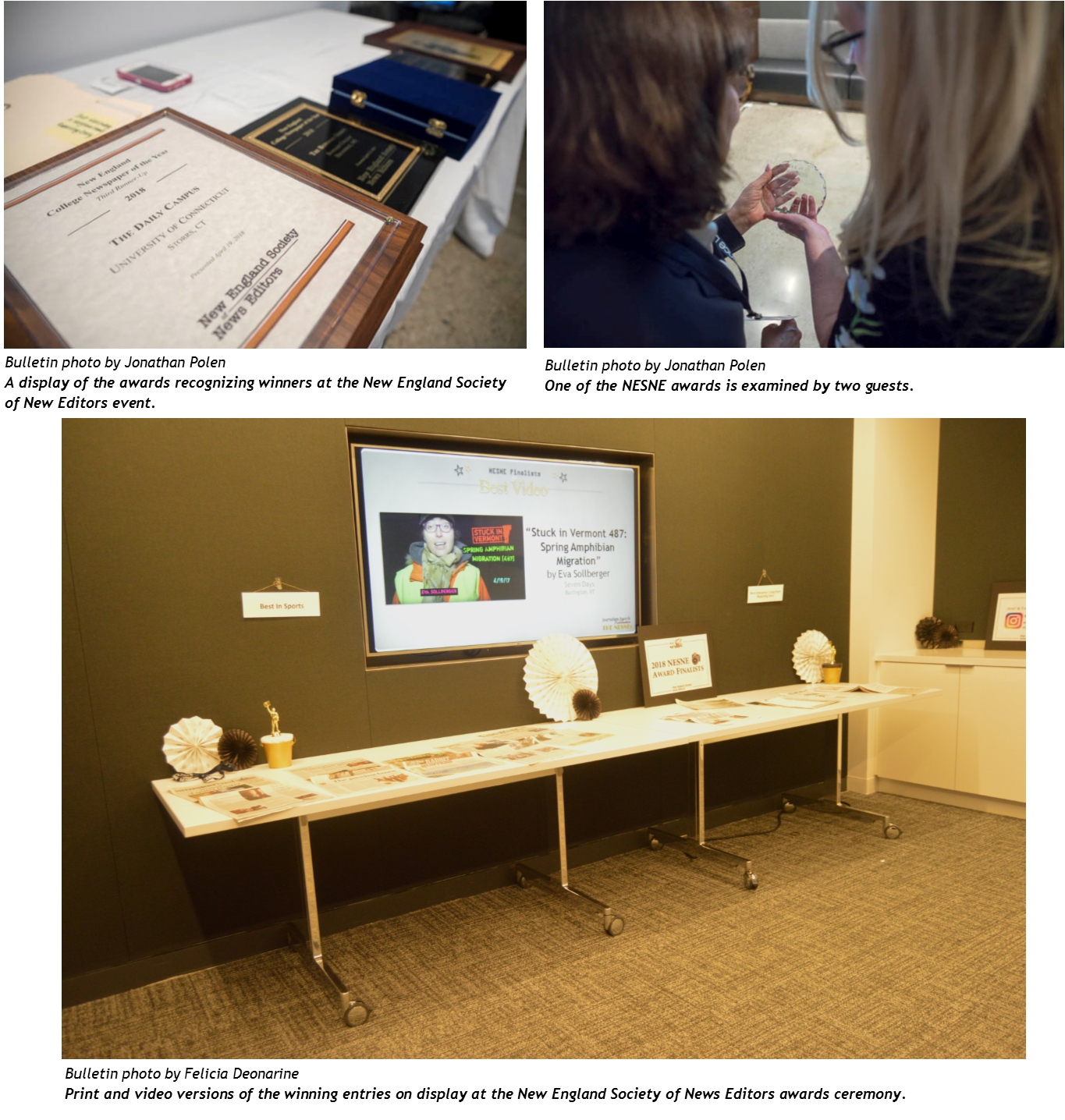

New England College Newspaper of the Year

The Bowdoin Orient, Bowdoin College

The Harvard Crimson, Harvard University, first runner-up

The Gatepost, Framingham State University, second runner-up

The Daily Campus, University of Connecticut, third runner-up

The NESNEs

Best Opinion or Commentary Writing

Winner:

Paul Choinierre, The Day, New London, Conn, for “Simmons goes Haberek”

Finalists:

New Hampshire Union Leader, Manchester, N.H., for “City Matters”

The Standard-Times, New Bedford, Mass., for “Editor gets life-changing payback”

The Hartford (Conn.) Courant, for “7 Reasons to Save Hartford”

Addison Independent, Middlebury, Vt., for “Does VTrans take advantage”

Best Hard News/General Reporting Story

Winner:

Christopher Williams, Sun Journal, Lewiston, Maine, for “Caged in Van No. 1304”

Finalists:

Sun Journal, Lewiston, Maine, for “Tell my family I love them”

Seven Days, Burlington, Vt., for “Death by Drugs”

The Colchester (Vt.) Sun, for “Paradise Lost”

The Patriot Ledger, Quincy, Mass., for “Who is the Real Scott Wolas?”

Best Feature Story

Winner:

Elodie Reed and Allie Morris, Concord (N.H.) Monitor, for “Living Transgender”

Finalists:

West Hartford (Conn.) LIFE, for “A story of horror and hope”

Seven Days, Burlington, Vt., for “Lucky Bums”

The Hartford (Conn.) Courant, for “Two Lives Shared”

Seven Days, Burlington, Vt., for “Life Sentence”

Best Enterprise/Long-Form Reporting Story

Winner:

Vanessa de la Torre and Matthew Kauffman, The Hartford (Conn.) Courant, for “Left Behind”

Finalists:

Sun Journal, Lewiston, Maine, for “Caged in Van No. 1304”

Boston Business Journal, for “Behind the Curtain”

The Providence (R.I.) Journal, for “Pot and Profit”

Worcester (Mass.) Magazine, for “In the Eye of the Commonwealth, landfill battle reaches fever pitch”

Best Watchdog or Neighborhood Reporting Story

Winner:

Tom Mooney and Jennifer Bogdan, The Providence (R.I.) Journal, for

“Children at Risk”

Finalists:

The Republican, Springfield, Mass., for “Officials refuse to release report on probe of police”

Daily Hampshire Gazette, Northampton, Mass., for “Under the Table”

The Hartford (Conn.) Courant, for “Left Behind”

The Hartford Courant, for “State probe finds misuse of tech school funds”

Best News Photo

Justin Pelletier, managing editor of the Sun Journal of Lewiston, Maine, who won the Best in Sports NESNE award, with Paula Bouknight, president of the New England Society of News Editors.

Winner:

Ken McGagh, The MetroWest Daily News, Framingham, Mass., for “Amputee Marine finishes Marathon”

Finalists:

The MetroWest Daily News, Framingham Mass., for “Helping hands at Marathon finish”

The Herald-News, Fall River, Mass., for “Rescue”

Brattleboro (Vt.) Reformer, for “ALS: The price on the body”

The Enterprise, Brockton, Mass., for “Heartbreaking”

Best Sports/Feature Photo

Winner:

Steve Heaslip, Cape Cod Times, Hyannis, Mass., for “Kennedy stamp dedication”

Finalists:

Telegram & Gazette, Worcester, Mass., for “Gardner’s homer lifts Shrewsbury”

The Inquirer and Mirror, Nantucket, Mass., for “Full Moon”

The Standard-Times, New Bedford, Mass., for “Touching up history”

Somerville (Mass.) Journal, for “Double head”

Best Video

Winner:

Peter Huoppi, The Day, New London, Conn., for “WiredZone: New-London-NFA Thanksgiving Game”

Finalists:

Brattleboro (Vt.) Reformer, for “Andy’s Journey: The Struggles through ALS”

The Hartford (Conn.) Courant, for “Rare conjoined twins seek ordinary life in extraordinary circumstances”

Seven Days, Burlington, Vt., for “Stuck In Vermont 460: River of Light”

Seven Days, for “Stuck In Vermont 487: Spring Amphibian Migration”

Best Digital Innovation

Winner:

Staff, Vineyard Gazette, Martha’s Vineyard, Mass., for “The Time Machine”

Finalists:

Cape Cod Times, Hyannis, Mass., for “JFK’s 100th Centennial”

The Standard-Times, New Bedford, Mass., for “www.southcoasttoday.com”

Best in Sports

Winner:

Justin Pelletier, Sun Journal, Lewiston, Maine, for “A quiet leader”

Finalists:

The Salem (Mass.) News, for “One of a Kind”

The Martha’s Vineyard Times, Vineyard Haven, Mass., for “The Last of the Rabbit Hunters”

The Republican-American, Waterbury, Conn., for “Marathon Man”

Telegram & Gazette, Worcester, Mass., for “The Passing Lanes”

Daniel Hovey

Daniel Hovey Peter Thomas Farrelly Jr.

Peter Thomas Farrelly Jr. James W. Morrissey Jr.

James W. Morrissey Jr. Mary Ellen (Monroe) Nihill

Mary Ellen (Monroe) Nihill Dave Behrens

Dave Behrens Mary Barker

Mary Barker John M. Noonan

John M. Noonan  Charles K. Goff

Charles K. Goff Joyce Ann (Baker) Cassinari

Joyce Ann (Baker) Cassinari Wendell H. Hawley

Wendell H. Hawley Roger F. LaFlamme

Roger F. LaFlamme  Barbara June Clarkson

Barbara June Clarkson