Donald Trump wasn’t at the New England Newspaper and Press Association winter convention, but he was much in evidence nevertheless.

Almost from its outset, the convention buzzed with an undercurrent of references — negative, but some humorous — to President Trump and his anti-press taunts. That climate surfaced even at the celebratory New England First Amendment Coalition’s awards luncheon on the convention’s first day, Friday, Feb. 24. It continued in a more full-throated way at one of the convention’s major events, Saturday, Feb. 25’s opening session — a panel discussion specifically designed to explore the press under Trump: “The next four years and the press.”

Both nights of the convention ended on the more usual and positive notes of applause, high-fives, hugs and standing ovations for the winners of awards in advertising, marketing and circulation Friday and in news Saturday.

Almost 150 guests attended the Friday evening awards, which featured 55 awards in 28 categories. On Saturday night, 375 people heard the names of 243 awards winners announced in 84 categories.

Linda Conway, NENPA’s executive director, said about 1,000 people attended the convention overall. It was held for the first time at the Boston Marriott Long Wharf hotel.

The convention featured a dozen vendors who showcased their products or services and 23 panel discussions or workshops, some of them geared to topics bearing on what a Trump administration could bode for the press and the First Amendment.

“I think there is always an interest in covering politics,” Conway said. “We did have sessions that leaned a little bit more towards that.

“What we try to do is offer different sort of tracks: editorial; business-side, geared toward increasing revenue and circulation; sessions geared toward legalities,” Conway said. “We hit the digital aspect as well – sessions on mobile. We try not to gear everything toward one specific track so that people can come from every aspect of newspapers. There’s something for everybody.”

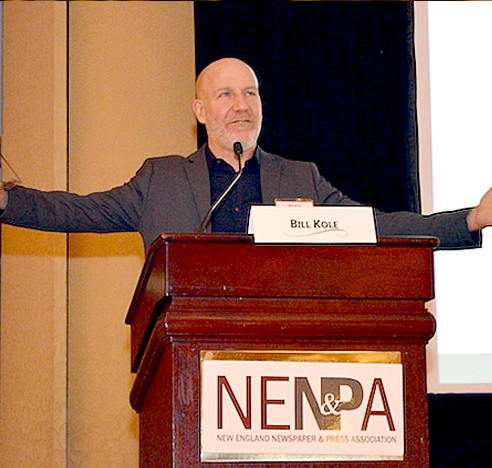

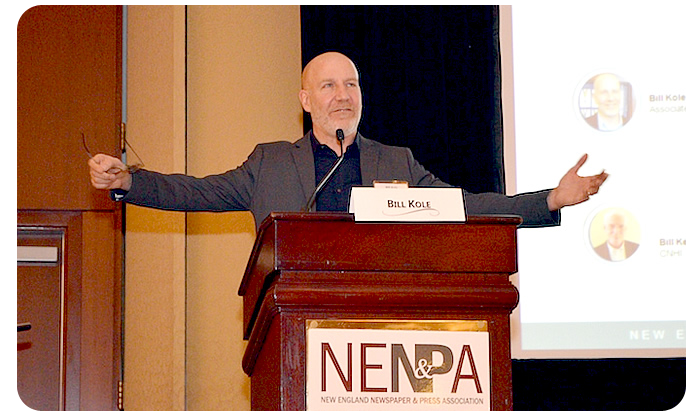

One sign of the prevalence of interest in the subject of Trump and press: The discussion on “The next four years and the press” was the best-attended of the 23 panels or workshops, with about 140 people present.

Bill Kole, New England news editor for The Associated Press, opened that discussion, which he moderated, by recounting what Trump had done or caused just in the prior 24 hours: “blasting … the media” for using anonymous sources; news organizations, including CNN and Buzzfeed, being barred from an informal press briefing at the White House; and Time Magazine and AP boycotting that briefing in protest.

Panelist Bill Ketter, vice president of news for Montgomery, Ala.-based Community Newspaper Holdings Inc., said: “We’re going through this period here where (Trump) has a base, a very strong base. He has played up that base, that base likes firming down on the press. That’s been only a month. Think of the next four years.”

Panelist Margaret Sullivan, media columnist for The Washington Post, noted that Trump recently “railed against the overuse of anonymous sources.” She called that “weird” in light of his comments during the presidential campaign about being a fan of WikiLeaks and his urging Russian hackers to leak Hillary Clinton’s emails.

“We have to get used to standing for something, and that something is democracy,” Sullivan said. “If we as journalists and news organizations are not going to defend press rights, I don’t know who’s going to do it. I don’t think we should be presenting ourselves as the opposition party.”

The day before, Sullivan received the Stephen Hamblett First Amendment Award at the New England First Amendment Coalition awards luncheon. Also presented at the luncheon were the Antonia Orfield Citizenship Award to Donna Green of Right to Know New Hampshire, and the Michael Donoghue Freedom of Information Award to the Sun Journal of Lewiston, Maine.

During her acceptance speech, Sullivan detailed threats posed by Trump. He has blacklisted news organizations, including the Washington Post, deemed unflattering stories to be fake news, called reporters scum, and asserted that the press is the enemy of the people, she said.

“President Trump shows no understanding of the role of the press in our democracy,” Sullivan said. “I’ve lost some sleep over it, worried about the very survival of American democracy when one of its foundations, a free press, is already under attack.”

The emcee at the luncheon also noted: “The president spoke at the Conservative Political Action Conference this morning, and he was at it again, calling us enemies of the people; we make up sources, we’re very dishonest people, apparently.”

That reference to what Trump calls journalists cropped up at other convention sessions, with speakers jokingly denying that they were “enemies of the people.”

At NENPA’s annual meeting Saturday morning, Feb. 25, Michael E. Schroeder, publisher of Central Connecticut Communications, based in New Britain and whose flagship is the New Britain Herald, was elected to succeed Mark S. Murphy, editor of the Providence (R.I.) Business News, as president of NENPA’s board of directors.

John Voket, associate editor of The Newtown (Conn.) Bee, was elected as the board’s vice president; Jeff Peterson, publisher of The Sun Chronicle of Attleboro, Mass., as treasurer; Sean Burke, formerly president and group publisher of Randolph, Mass.-based GateHouse Media New England, as secretary.

James Normandin, chief operating officer of the Manchester, N.H.-based Union Leader Corp., was elected as a member of the board.

Earlier in the meeting, attended by about 15 people, Linda Conway said in her report as NENPA’s executive director that 445 people registered to attend sessions at this year’s winter convention. There were 375 guests registered for the journalism awards banquet Saturday night, Feb. 25; 145 for the Friday night ceremony for advertising, circulation and marketing awards; 275 for the New England First Amendment Coalition’s awards luncheon Friday; and 80 for the New England Newspaper Hall of Fame dinner Friday night, she said.

This year, there were 3,226 entries for the awards contests, up from 3,176 in 2016, Conway said.

About 200 people attended the New England Newspaper Fall Conference in October, down about 15 from the attendance in 2016, she said. Attendance at the Yankee Quill Awards dinner at the conference was up slightly, however, as was the number of entries in the fall conference awards contests, Conway said.

Applications for journalism scholarships granted by a NENPA affiliate organization topped 100, a record, she said. Nominations for induction into the Hall of Fame were up to their highest level too, Conway said.

Conway asked for comments about this year’s convention. The responses included references to “big turnouts” at convention sessions; praise for the effectiveness of signs directing people to convention events; and a compliment for the convention’s being “well-thought-through.”

In an interview after the convention, Conway said: “We had a great turnout for the convention. It was in line with the numbers we’ve had with the last couple of years. Everybody came out of energized and really liked the sessions … ”

The weekend’s sunny weather complemented the convention’s location on Boston Harbor.

“It was a great location, close to everything,” Conway said. “The weather cooperated so people could go outside of the hotel. We had many, many people come up and say that they loved the location.

“All of the reactions and comments have been really positive,” she said. “Everybody seemed to enjoy it. We had people from outside of the industry to help us look at our industry from a different perspective.”

Following are the key award winners for advertising, circulation, and marketing presented Friday night, Feb. 24:

Best Ad Designer, daily: Annie Sharples, The Day, New London, Conn.

Business Innovation, daily: Vineyard Gazette, Martha’s Vineyard, Mass.

Advertising General Excellence, specialty: Bay State Parent, Millbury, Mass.

Advertising General Excellence, weekly: The Vermont Standard, Woodstock, Vt.

Following are the key awards winners for news presented Saturday night, Feb. 25:

Rookie of the Year, weekly: Kymelya Sari, Seven Days, Burlington, Vt.

Rookie of the Year, daily: Elaine Ezerins, St. Albans (Vt.) Messenger

Photojournalist of the Year, weekly: Robin Chan, Hingham (Mass.) Journal

Photojournalist of the Year, daily: Merrily Cassidy, Cape Cod Times, Hyannis, Mass.

Reporter of the Year, weekly: Walter Bird Jr., Worcester (Mass.) Magazine

Reporter of the Year, daily: Doug Fraser, Cape Cod Times, Hyannis, Mass.

General Excellence, specialty publications: Boston Business Journal

General Excellence, smaller weekly: Mount Desert Islander, Bar Harbor, Maine

General Excellence, larger weekly: Seven Days, Burlington, Vt.

General Excellence, smaller daily: MetroWest Daily News, Framingham, Mass.

General Excellence, larger daily: Republican-American, Waterbury, Conn.

At long last, the stuff of journalism

Gene Policinski, inside the First Amendment

Gene Policinski is chief operating officer of the Newseum Institute and senior vice president of the Institute’s First Amendment Center. He can be reached at gpolicinski@newseum.org.

Follow him on Twitter:

@genefac

The resignation of National Security Adviser Michael Flynn. White House internal disputes that stall policy decisions. Even a mini-crisis involving North Korea.

At long last: the stuff of journalism.

After seeming eons of the squishiness of reporting on campaign claims and counterclaims, email investigations that went nowhere, and distractions including faux-home TV shopping pitches, late-night tweets and daytime insults, a free press is now in full operating mode in the role that the nation’s founders intended: as a watchdog on government.

The fact is that in an era when even the existence of “facts” is seriously debated, the nation’s news media is doing its job by keeping its fellow citizens informed and holding government official accountable — most recently around Flynn’s departure, with questions that echo the fabled inquiry of Watergate: “What did the President know, and when did he know it?”

About a week ago, The Washington Post reported that Flynn might have discussed the Obama administration’s sanctions against Russia with the Russian ambassador, an action that would have been inappropriate and possibly even illegal at the time it took place. The White House knew for weeks of Flynn’s compromising behavior — but with the Post report, we knew it.

The latest news is the White House’s fierce condemnation of the leaks that brought about Flynn’s resignation. The press has pushed back, calling it a move to focus blame on those who revealed Flynn’s conduct rather than the conduct itself. That anti-media message was nonetheless fully reported by the same “fake media” that Trump targeted.

And then there was North Korea’s surprise launch of an intermediate-range ICBM missile during a U.S. visit by Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Along with that news, reporters and photographers conveyed to Americans how their new president handled the moment — from “live” images of the terse statement of support for Japan, to the casual approach to discussing national security at a resort restaurant table, in full view of other diners.

Notice please, no mention here of “Saturday Night Live” sketches, late-night comedy monologues, social media rants gone viral or “alt-right” opinion operations. Let’s defend those as a vigorous, vital part of free speech, or even — in a stretch — as covered by the free press protections for opinion on matters of public interest. But none are Journalism with a big “J.”

No doubt this favorable view of how journalists operate on our behalf won’t be shared by the sizeable numbers of those who simply dislike or distrust the press. And Trump and Co. continue to send mixed signals about Flynn’s resignation and reporting around it: From counselor Kellyanne Conway’s “100 percent” support of Flynn, to Press Secretary Sean Spicer’s statement about an hour later that Trump demanded Flynn’s resignation because of an “eroding level of trust,” to Trump’s complaint that “fake media” conspired with rogue members of the intelligence community to get Flynn fired, followed by a rambling broadside against the media at an extended press conference.

But the fact (that word again) is that our nation’s first leaders faced a press more antagonistic than today’s mainstream media — a press that regularly dealt in “fake news” and gleefully manufactured scandals — and still went the extra mile to create unprecedented protections for what we say and write, and what we report and offer our opinions about.

By the way, that “we” is you, me and the blogger next door, as well as the national news outlets, and the local newspapers and radio stations. Once we get information — from the president or from leaks — we’re free to tell others about it. Self-governing societies require that free flow of information, versus government handouts or news blackouts.

Martin Baron, the Washington Post’s executive editor, was called on Feb. 15 at the Code Media conference in California to both explain and defend the Post’s approach to reporting on the Trump administration.

Baron’s response: “We’re not at war with the administration, we’re at work. We’re doing our jobs.”

Baron also said the news media, overall, “are too competitive with each other to behave in any way like a party … we’re not the opposition either. We’re independent.”

In addition to paying attention to what the press is reporting, we ought to be celebrating that independence — from the Post to Fox News to MSNBC’s “Morning Joe” to CNN to The Wall Street Journal to “Fox & Friends” to Breitbart News. The “marketplace of ideas” is alive in the Digital Age.

Lest this be considered unrestrained adoration of all journalism, let’s agree that there is plenty to be critical of in this wild, disruptive era of new tech, social media and upside-down finances behind most media operations. To name a few examples: the often seamy “reports” by online outlets like the former Gawker site, the decision by BuzzFeed to report unsupported allegations about President Trump, and the well-aired rumors about First Lady Melania Trump.

And there are the ongoing questions since the dawn of the Republic over media ethics, good taste, accuracy, fairness, and — to borrow a useful phrase coined by comedian Stephen Colbert — “truthiness.”

But let’s hear it today for the free press. Here’s a final fact: Right now, the news media is showing the nation what the “news” part of that name means.