By Siyi Zhao, Bulletin Staff

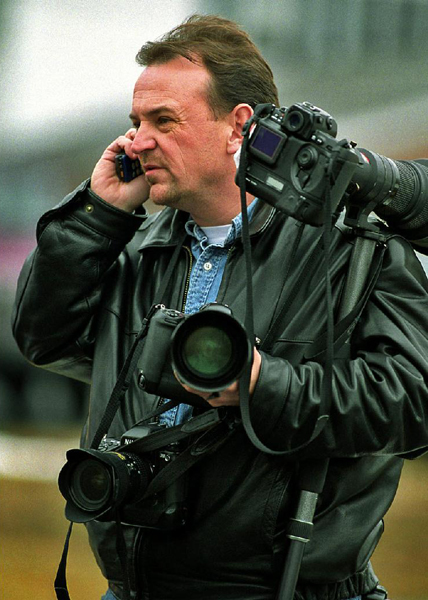

John Tlumacki’s photo of the aftermath of the bomb that exploded near the Boston Marathon finish line became an iconic scene from the terrorist tragedy.

John Tlumacki kept seeing the photographs he took in the grisly aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombings playing like a slideshow in his head over and over, images of people crying for help and helping each other deal with their injuries. Those nightmares began almost a month after the bombings.

“The camera became my enemy,” said Tlumacki, a longtime Boston Globe photojournalist. “I didn’t even want to pick it up anymore … ”

Tlumacki said he became angry as he was taking photographs of all the carnage, figuring that it was the result of an act of terrorism.

As much as Tlumacki tried to deny it, he said he knew he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Three people died and nearly 270 were injured in the April 2013 bombings near the Boston Marathon’s finish line on Boylston Street.

The Marathon bombings were among the latest instances in which reporters covered scenes of multiple deaths and destruction. New England has experienced others in the not-too-distant past.

In December 2012, 20 children and six adult staff members were shot to death at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. And in February 2003, 100 people were killed and 230 people were injured during The Station nightclub fire in West Warwick, R.I.

Part of being a journalist is covering traumatic events like those. According to experts interviewed by the Bulletin, reporters should treat such events not only as professionals, but also as human beings.

George Everly Jr., an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, said the more preparation journalists can have in dealing with stressful or traumatic events, the more they will understand what they could confront on the job.

“Before someone goes into this career, that’s when you prepare,” Everly said. “That should be an obligation that schools of journalism should have. We have to do a better job setting appropriate expectations, because this kind of work is not for everyone. Some people are just not suited for it. And they should know that upfront.”

According to “Covering Trauma: Impact on Journalists,” an overview of current research on the danger for journalists focusing on traumatic events, most journalists exhibit resilience in the face of traumatic events. But a significant minority might be at risk of having long-term psychological problems.

For some journalists, the more they are exposed to such events during their career, the more resilient they become, experts interviewed said. Still, there are other journalists who become more traumatized the more they are exposed to trauma.

“For many reasons, some people prove to be more resilient in the face of trauma than others,” said Jim MacMillan, program manager at the Center for Public Interest Journalism at Temple University.

Cait McMahon, an Australian psychologist and managing director at the Dart Center Asia Pacific, said in an email that the different reactions to trauma can be traced to many factors. Those factors include the journalist’s trauma history and mental health history, and the severity of the traumatic exposure and isolation the journalist experienced.

The Dart Center, which focuses on informed, innovative and ethical reporting on violence, conflict and tragedy, has tip sheets available for reporters on how to cope with different traumas, such as losing a colleague or managing the stress of a long investigation.

McMahon said social support is one of the factors that can help build resilience. Journalists who can count on a colleague, friend or family member for support after covering a traumatic event seem to cope much better than those who are isolated and don’t have such support.

Matthew Kauffman covered suicides among soldiers during war and the Sandy Hook school shootings for The Hartford (Conn.) Courant. He spoke to relatives of soldiers who killed themselves in Iraq and Afghanistan and was in the newsroom collecting information about the Newtown shootings.

Kauffman found that talking to people after a traumatic event helped him process the difficult information on which he was reporting.

“It’s not about forgetting. It’s about making it easier to remember,” Kauffman said. “It’s about making it less emotional or painful to remember. Each time, I felt less uncomfortable to talk about it.”

Some journalists think that the responsibility for them to cover events and accurately report on them to readers helps safeguard them from being affected psychologically.

“I don’t feel like I am psychologically affected by … traumatic events,” said Mark Arsenault, a Boston Globe reporter who covered the Station nightclub fire in Rhode Island.

He witnessed the rescue and recovery operation at the scene.

“Sometimes it’s sad, but I don’t feel like it’s a lasting thing. Because I am the representative of the readers, and the readers need people who are the best, people who can do things without becoming personally affected. And becoming personally affected compromises your ability to do a fair and accurate job of telling,” Arsenault said.

Sometimes, however, even journalists who at the time of a traumatic incident focus first on their professional obligation to report on the incident might suffer post-traumatic stress disorder, as happened to Tlumacki.

“I think I totally took it all in. I became a part of it,” Tlumacki said of his feelings while photographing the Boston Marathon bombing scene.

He was standing on the finish line, about 40 feet from the first bomb and photographed Krystle Campbell, one of the three people killed in the bombing, through the smoke.

“My emotion ranged from being very angry to being persistent and doing my job, worrying about whether I was going to be kicked out before I had any photos. When you have that thought in your head, you resign (yourself) to the fact that maybe something is going to happen to you. I just want to keep doing my job. I realize it was my responsibility to show the world what happened. The consequence is to deal with trauma and live with it,” Tlumacki said.

Other than professional help from psychologists, journalists might choose some self-help strategies to cope with problems caused by traumatic events, Everly, the John Hopkins psychiatry professor, said.

To cope with his stress, Tlumacki went to Sedona, Ariz., with his wife seven months after the bombings.

He said of the trip: “It was visually exciting, and it’s beautiful. I needed to get away from work and to see something beautiful and be in nature.”

Tlumacki said the beauty in Sedona prompted him to capture that beauty with his camera.

“I had to take some beautiful photos,” Tlumacki said. The camera “became my friend again.”

‘I think I totally took it all in. I became a part of it.’

–John Tlumacki

‘My emotion ranged from being very angry to being persistent and doing my job, worrying about whether I was going to be kicked out before I had any photos. When you have that through in your head, you resign (yourself) to the fact that maybe something is going to happen to you. I just want to keep doing my job. I realize it was my responsibility to show the world what happened. The consequence is to deal with trauma and live with it.’

–John Tlumacki, Photojournalist

Boston Globe

‘It’s not about forgetting. It’s about making it easier to remember. It’s about making it less emotional or painful to remember. Each time, I felt less uncomfortable to talk about it.’

–Matthew Kauffman, Reporter

Hartford (Conn.) Courant

‘For many reasons, some people prove to be more resilient in the face of trauma than others.’

–Jim MacMillan, Program manager

Center for Public Interest Journalism, Temple University

‘Sometimes it’s sad, but I don’t feel like it’s a lasting thing. Because I am the representative of the readers, and the readers need people who are the best, people who can do things without becoming personally affected. And becoming personally affected compromises your ability to do a fair and accurate job of telling.’

–Mark Arsenault, Reporter

Boston Globe

‘Before someone goes into this career, that’s when you prepare. That should be an obligation that schools of journalism should have. We have to do a better job setting appropriate expectations, because this kind of work is not for everyone. Some people are just not suited for it. And they should know that upfront.’

–George Everly Jr., Associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences

John Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore MD