By Alejandro Serrano

and Nadine El-Bawab,

Bulletin Correspondent

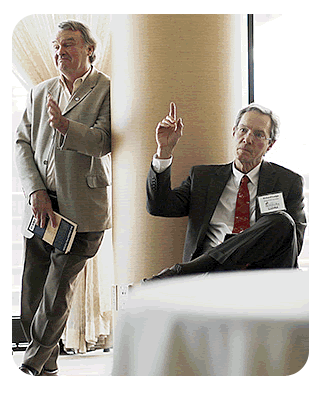

Panelist Stephen Kurkjian, center, shares a laugh with fellow panelists Kevin Landrigan and Anne Karolyi.

For Stephen Kurkjian, a three-time Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter, dealing with a source is a lot like an arm-wrestling match.

“It is important you conduct yourself with professional(ism) and graciousness,” he said at a panel discussion Saturday, Feb. 25, on “A Source Guide: How to choose, reach and max out your news sources” at the New England Newspaper and Press Association winter convention.

The match is about balance between giving and getting, Kurkjian said. Terms of engagement should be set at the beginning of the relationship, as a reporter tiptoes the line of almost being friends with a source, while carefully avoiding actually being one.

He advised being prepared before meeting with a source and making sure never to promise a source a flattering story.

Kurkjian, a retired investigative reporter for The Boston Globe, was one of four panelists. The others were Shelley Murphy, a Boston Globe reporter who shared in the Globe staff’s Pulitzer Prize for breaking-news coverage of the Boston Marathon bombings; Kevin Landrigan, a veteran, award-winning political reporter now with the New Hampshire Union Leader of Manchester; and Anne Karolyi, managing editor of the Republican-American of Waterbury, Conn., which won the top prize for large daily newspapers at the convention’s news awards ceremony that night.

The panelists used personal experiences in discussing how to work with difficult sources and cultivate lasting relationships on a beat.

Karolyi discussed the Republican-American’s policy of avoiding the use of anonymous sources. She said the only rare exceptions to the Republican-American’s policy include an overriding importance for the public to know something or if every other way of obtaining the same information on the record had been tried to no avail.

An anonymous source can be a great starting point for a reporter, but the reporter must fact-check the information, whether by obtaining a public record or obtaining the information from another source who will speak on the record, she said.

“It does make it harder,” Karolyi said. “It’s not fatal, just much more work.”

Karolyi said many journalists at the Republican-American have gone on to well-known news organizations, and those reporters have told her that being forced to work harder to back up their stories made them better reporters.

Murphy said the Globe doesn’t like unidentified or confidential sources, and neither does the public. She said, however, that sometimes a reporter must promise a source confidentiality because of the nature of a story. But generally, the only promise a reporter should make is that a story will be fair, Murphy said.

“I make sure that people know this is what I am writing,” Murphy said. “I never promise anyone a favorable story, but I promise them that it will be fair.”

Murphy cautioned those in the audience to avoid being used as a reporter.

Being a reporter is “all built on trust,” Murphy said.

Kurkjian said too that trust is integral to reporting stories fairly. A reporter must get to know the source and let the source know that the reporter cares and respects the source, and that the reporter expects that to be reciprocated by being trusted to get a story right, he said.

“That’s what the weekends are for,” he said about learning the jargon some sources use.

The more than 65 people who attended the discussion were encouraged to participate in the discussion. An audience member asked the panelists how to penetrate and cover a police department that is reluctant to provide information to the press.

Kurkjian returned to his point of trust and fairness.

“You’re the most important person in the town – not the chief,” he said.

Murphy suggested seeking out police officers “who have been disciplined because they are usually the ones who are unhappy,” and that there are always people in the police department “that want to talk; tell them that they can trust you.”

Maneuvering through different sources who are connected to a hard-to-reach source might help in getting that difficult source to talk with a reporter, said Landrigan, who in covering New Hampshire’s presidential primaries has interviewed every president since 1980.

Sometimes asking sources you are on good terms with to reach out to the difficult source might also help, he said.

Reporters should acquaint themselves with their state’s shield laws, which allow a journalist to keep confidential sources confidential. Landrigan said that when he is reporting in New Hampshire, he can promise a source confidentiality, but he can’t promise that he won’t face court action if he refuses to identify a confidential source.

Nonetheless, he said a story shouldn’t hinge on one unidentified source and that if someone’s top concern is confidentiality, then he or she isn’t very committed to releasing information and the reporter should find more sources.

The workshop shed light on the balance Kurkjian mentioned when comparing the use of sources to an arm-wrestling match.

“It is a match of wits … but always handle yourself professionally,” he said.

(A handout with 10 tips for dealing with news sources was distributed to audience members after the panel discussion ended.)

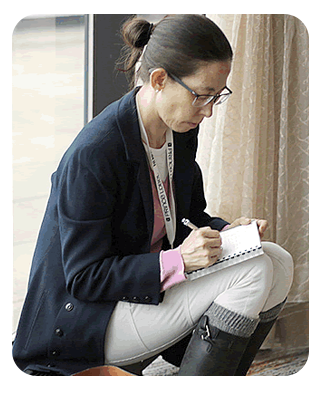

Fellow panelists listen as Kevin Landrigan makes a point to audience members, some of whom took notes and asked questions.