I don’t know about you, but my life seems to get busier with each passing day.

I don’t know about you, but my life seems to get busier with each passing day.

I just finished publishing my second book in a month, began work on a major project to help raise money for a press association, conducted more webinars than I can remember during the past few weeks, and summer convention season kicks in tomorrow, even though summer is still a few weeks away.

My email is filled with messages each day from publishers and other newspaper colleagues who want advice about something going on at their papers. The questions come from the tiniest papers with just one or two folks, including the publisher, on staff, to folks running large regional and national groups.

If you think it sounds a little overwhelming, you’re right. I recently read a biography of George Washington and learned, not surprisingly, he often felt as if he was in over his head. I know the feeling, George. I’m sure many of us share the same emotion.

Like a lot of people in our business, I sometimes want to throw my hands in the air and ask, “Am I really making any difference at all?”

Then someone like Joey Young, comes along. You’ve probably heard of Joey, the “whiz kid” from Kansas who keeps creating successful community newspapers in defiance of the choruses of “You can’t do that.” Joey has a habit of reminding me how well things are going in Kansas.

Then there are the publishers, editors and ad managers lining up at conventions to tell me how well their papers are doing, while everyone seems to be telling them they should be dying.

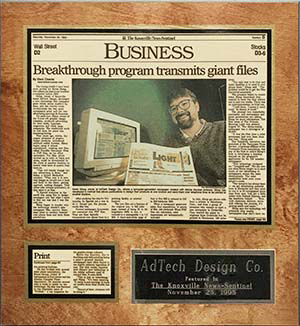

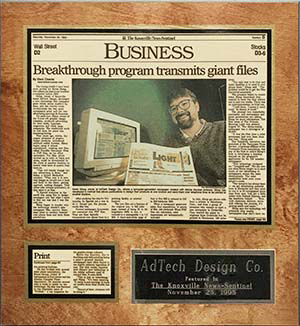

I remember hearing from the CEO of Adobe Software several years ago. He wrote to thank me for the work I had done to make Acrobat a viable product. He told me, “What you did may have saved our company.”

I was looking for an email yesterday and was surprised to find a five-year-old message from a business leader in New Orleans who was excited about a plan I had created, at his group’s request, to lure a new daily

newspaper to the city after its long-standing daily newspaper moved to a digital-first format, abandoning their traditional daily model.

I felt a rush of adrenaline as I read the words he wrote five years ago: “I love it!”

Those of you who know me well know that one of my degrees is in theology, and I love keeping up with what various groups believe. I often say I have a little Quaker in me, even though I’m not Quaker, because I love the Quaker belief that a single individual, even when standing alone against great opposition, has a significant chance of being right.

When I was being told no one would ever print a newspaper ad or page from a PDF file, by the very people I thought would be most excited about the possibility, those voices didn’t sway me. That’s one of the things the head of Adobe thanked me for all those years ago.

When I read, as we all do, that newspapers are dying, it doesn’t slow me down, because I know the truth.

Two months ago, a friend told me he attended a civic club meeting and the guest speaker was the daily

newspaper editor from his town. My friend told me he was shocked when the editor told the group that

newspapers were near death and they would be better off to find alternative sources, primarily online news sites, to get their information.

My friend was surprised that I wasn’t surprised. It’s enough to get a guy down, but not me. At least not for long.

I just think about Roger Holmes and those papers in Western Canada and his work to move them back into local hands. And I think about Victor Parkins in Tennessee, whom I just got off the phone with, and his papers. He told me they are doing really well, increasingly better each year.

I think about some of the biggest names in the business who contact me to let me know they read my columns and agree with my thoughts that local management of newspapers is the only way to keep them successful.

Last night, I was on the phone with legendary newspaper consultant Ed Henninger. We talk almost every day. The conversation moved toward the topic of newspapers, as it always does, and our concern for groups that continually press the “newspaper is dying” message.

Then Ed told me about one of the national newspaper groups he works with as a consultant.

He said, “You know what the difference is with them, and why I like working with their group?”

Obviously I asked.

“The difference is, they leave the management of their papers in the hands of the publishers and staffs, and they have good newspapers because they do.”

I know I’m preaching to the choir, but sometimes the choir needs to be reminded that they sound good.

The printed word isn’t dying. You can find the books I publish in bookstores and all the usual online retailers.

The printed versions outsell the digital versions by a long shot. Most of the studies I find show a 4 percent drop in digital book sales during the past year.

Why have some of our brethren fallen for the “print is dead” line? Well, that’s another column for another day. My 800 words were used up 90 words ago.

I don’t know about you, but my life seems to get busier with each passing day.

I just finished publishing my second book in a month, began work on a major project to help raise money for a press association, conducted more webinars than I can remember during the past few weeks, and summer convention season kicks in tomorrow, even though summer is still a few weeks away.

My email is filled with messages each day from publishers and other newspaper colleagues who want advice about something going on at their papers. The questions come from the tiniest papers with just one or two folks, including the publisher, on staff, to folks running large regional and national groups.

If you think it sounds a little overwhelming, you’re right. I recently read a biography of George Washington and learned, not surprisingly, he often felt as if he was in over his head. I know the feeling, George. I’m sure many of us share the same emotion.

Like a lot of people in our business, I sometimes want to throw my hands in the air and ask, “Am I really making any difference at all?”

Then someone like Joey Young, comes along. You’ve probably heard of Joey, the “whiz kid” from Kansas who keeps creating successful community newspapers in defiance of the choruses of “You can’t do that.” Joey has a habit of reminding me how well things are going in Kansas.

Then there are the publishers, editors and ad managers lining up at conventions to tell me how well their papers are doing, while everyone seems to be telling them they should be dying.

I remember hearing from the CEO of Adobe Software several years ago. He wrote to thank me for the work I had done to make Acrobat a viable product. He told me, “What you did may have saved our company.”

I was looking for an email yesterday and was surprised to find a five-year-old message from a business leader in New Orleans who was excited about a plan I had created, at his group’s request, to lure a new daily

newspaper to the city after its long-standing daily newspaper moved to a digital-first format, abandoning their traditional daily model.

I felt a rush of adrenaline as I read the words he wrote five years ago: “I love it!”

Those of you who know me well know that one of my degrees is in theology, and I love keeping up with what various groups believe. I often say I have a little Quaker in me, even though I’m not Quaker, because I love the Quaker belief that a single individual, even when standing alone against great opposition, has a significant chance of being right.

When I was being told no one would ever print a newspaper ad or page from a PDF file, by the very people I thought would be most excited about the possibility, those voices didn’t sway me. That’s one of the things the head of Adobe thanked me for all those years ago.

When I read, as we all do, that newspapers are dying, it doesn’t slow me down, because I know the truth.

Two months ago, a friend told me he attended a civic club meeting and the guest speaker was the daily

newspaper editor from his town. My friend told me he was shocked when the editor told the group that

newspapers were near death and they would be better off to find alternative sources, primarily online news sites, to get their information.

My friend was surprised that I wasn’t surprised. It’s enough to get a guy down, but not me. At least not for long.

I just think about Roger Holmes and those papers in Western Canada and his work to move them back into local hands. And I think about Victor Parkins in Tennessee, whom I just got off the phone with, and his papers. He told me they are doing really well, increasingly better each year.

I think about some of the biggest names in the business who contact me to let me know they read my columns and agree with my thoughts that local management of newspapers is the only way to keep them successful.

Last night, I was on the phone with legendary newspaper consultant Ed Henninger. We talk almost every day. The conversation moved toward the topic of newspapers, as it always does, and our concern for groups that continually press the “newspaper is dying” message.

Then Ed told me about one of the national newspaper groups he works with as a consultant.

He said, “You know what the difference is with them, and why I like working with their group?”

Obviously I asked.

“The difference is, they leave the management of their papers in the hands of the publishers and staffs, and they have good newspapers because they do.”

I know I’m preaching to the choir, but sometimes the choir needs to be reminded that they sound good.

The printed word isn’t dying. You can find the books I publish in bookstores and all the usual online retailers.

The printed versions outsell the digital versions by a long shot. Most of the studies I find show a 4 percent drop in digital book sales during the past year.

Why have some of our brethren fallen for the “print is dead” line? Well, that’s another column for another day. My 800 words were used up 90 words ago.

What is the key to creating an award-winning piece of journalism?

What is the key to creating an award-winning piece of journalism?

I don’t know about you, but my life seems to get busier with each passing day.

I don’t know about you, but my life seems to get busier with each passing day.